At Merlin, as the dark nights are drawing in and Autumn is in full swing, we have been thinking about our past travels, in particular our favourite geological localities. Some are closer to home, whilst others are more far-flung. Take a look at where we have picked. Have you been to any before or are they on your list of places to visit in the future? Where is your favourite place for a little geoliday?

Closer to home:

John Donato has picked two locations in Dorset:

Ballard Down Fault:

Ballard Down Fault is a beautiful, curved fault plane with vertically-bedded chalk to the South (left) and north-dipping chalk to the North (right). The fault has puzzled geologists for many years. Recent interpretation (Underhill and Paterson, 1998) suggests that tightening of the monoclinal fold during late-stage structural inversion produces space compression resulting in an ‘out-of-syncline’ backthrust. Drawing a coherent cross section to illustrate this model is not easy. You might decide, as I have, that the orientation of the fault does not fit well with this model. In which case, the puzzling continues! The fault can best be seen from the sea. Fortunately, a ‘geological excursion’ on the Swanage-Poole ferry permits a good vantage point and allows refreshment at one or two of the excellent pubs/restaurants in Poole Harbour (pandemic permitting). The fault can then be enjoyed again on the return trip!

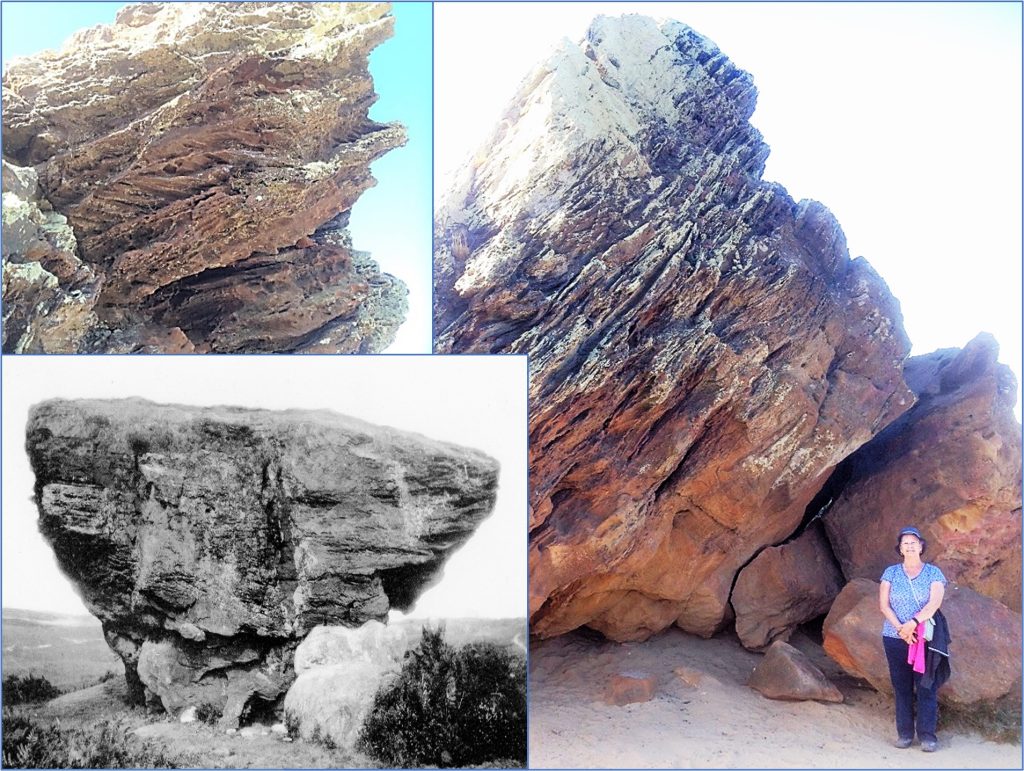

Agglestone Rock:

Agglestone Rock is a large, toppled pedestal rock of Eocene age located approximately 1km south of the Purbeck Hills Golf Course in Dorset. It is easily accessible from public footpaths crossing Godlingstone Heath. The upper part of the Rock shows current bedding within hard ferruginous grits and sandstones. The lower part is a more massive, and much softer, sandstone. The lower interval was probably mined at some time, and this may have contributed to the pedestal shape. It is true that, in old Dorset dialect, ‘to aggle’ means to wobble, but the legend is perhaps not true that the rock was thrown by the Devil from the Needles on the Isle of Wight, aiming at Corfe Castle.

Georgie Lockham: Wren’s Nest

My favourite geological locality is the Wren’s Nest National Nature Reserve in Dudley, West Midlands. It was one of the first geological sites I visited whilst on an A-level geology trip, and is only five minutes from where I grew up. It was through visiting this outcrop, and others in my local area, that sparked my interest in geology.

The Wren’s Nest was the World’s first ever National Nature Reserve, and later became a Site of Special Scientific Interest. Interbedded limestones, mudstones and shales deposited during the Silurian period and later folded into an anticline during the Variscan Orogeny, create the steeply dipping strata seen outcropping today. The limestones are abundant with fossils, which are so important to the geological community that the site had to be protected. In total over 700 types have been discovered, with 186 being found for the first time here, and just under half of these are unique to the site. Anyone can go to the Wren’s Nest in search of fossils, from experts to school children. Fossil collecting is limited to the loose material, but you can still find lots of crinoids, corals, brachiopods, bivalves and gastropods. A huge bed displaying ripples marks is also quite spectacular. However, the most famous fossil of all found at the Wren’s Nest is the trilobite Calymene blumenbachii, also know as the ‘Dudley Bug’. You would be extremely lucky to find a good specimen now, but it is so important to Dudley you can see it on the Coat of Arms.

For leaflets and information on visiting, click here.

Further afield:

Eleanor Oldham: Table Mountain

For many years, Table Mountain in Cape Town occupied the number 1 slot on my list of places I wanted to visit. When I finally got there, it was as impressive as I’d imagined.

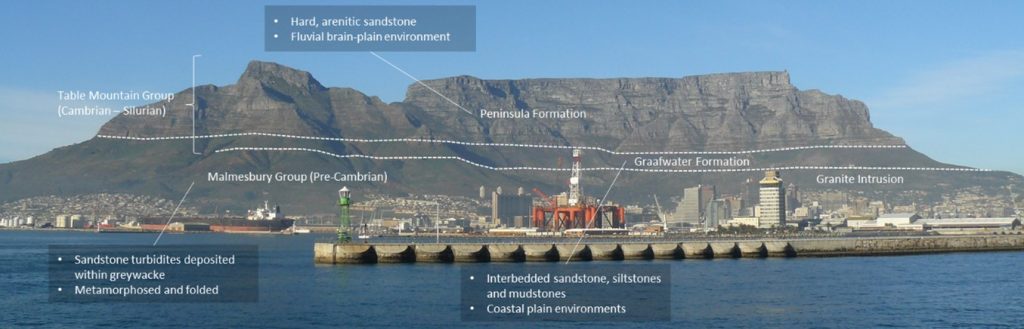

Viewed from the Cape Town side, Table Mountain really lives up to its name and looks as flat as a tabletop. The “top of the table” is made up of hard, arenitic sandstones of the Ordovician-aged Peninsula Formation (part of the Table Mountain Group). The orogenic event responsible for the Cape Fold Belt occurred during the Carboniferous – early Permian, so it is thanks to the hard nature of the Peninsula Sandstones that Table Mountain has been able to endure for so long.

That’s not to say that a significant amount of erosion hasn’t occurred. If you take the cable-car to the top of Table Mountain you can see the rock has been weathered into an irregular topography, providing interesting niches for local plants to colonise. Indeed, if you travel to Camp’s Bay and peak at the side of Table Mountain, it no longer looks flat at all! Millions of years of erosion have carved out large drainage valleys, leaving an extremely rugose unconformity surface. I was fascinated to discover that the top of Table Mountain is actually the syncline portion of a fold. This explains the horizontal looking layering but also indicates a phenomenal amount of erosion has already occurred to reach the present-day appearance.

Left: The top of Table Mountain. Right: Table Mountain from the Camp’s Bay side.

I could write pages of material describing the geological details of Table Mountain and the wider region, but it is the beauty of the mountain which gives it such enduring appeal. In my opinion, it is worthy of a top position on the list of geological pilgrimages.

Helen Bone: New Zealand Volcanoes

I’m not sure why volcanoes have always fascinated me, I guess it’s their sheer power and unpredictability which makes them one of natures unsolved mysteries in many ways. When erupting they seem to move so slowly but are largely an unstoppable force. It was with some excitement therefore, that I visited New Zealand and actually got to see some first-hand. Even at a distance Mount Ruapehu, located in the Central Plateau of New Zealand’s north island, is an imposing feature on the landscape. This perhaps explains why it was picked to feature in the Lord of the Rings films as Mount Doom. It is the largest active volcano in New Zealand with three major peaks (between 2,751 and 2,797 m high). The most recent 2007 eruption lasted less than a minute but blasted ash, mud and rocks 2km out from the crater lake.

From the freezing cold of the peaks it is not far to reach the geothermal valleys around the central plateau area. Here steam rises up from lakes, and bubbling mud can be heard as you walk around volcanic areas further attesting to the areas volcanic power. It should come as no surprise that all this geothermal power is being harnessed to provide a green source of both heat and electricity for the country.